I take a run at historical fiction in light of MDOT’s plans to remove I-375 and in the process discuss necessity and public use concepts.

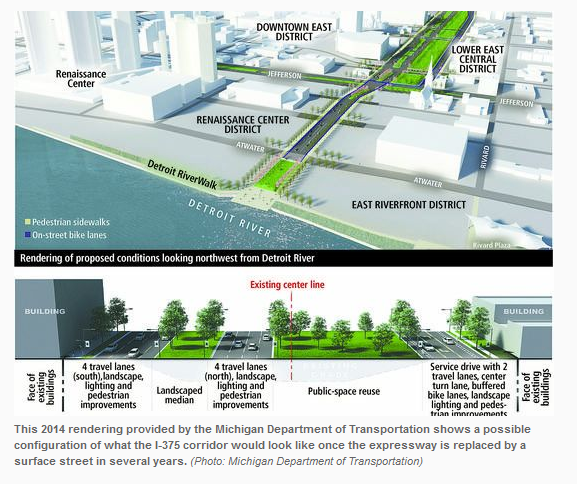

The Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) recently announced that it is proceeding with its plan to remove I-375, which is a spur from I-75 south into downtown Detroit. MDOT intends to create a surface street in its place that includes green space.

The decision is applauded by planners. For example, this article, by an urban studies and planning professor at Wayne State University, describes the motivation behind the decision. “Planners thought that if suburban residents could get in and out of the city more easily and quickly, the downtown would be more competitive as a shopping and office destination. Urban cut-through freeways succeeded in increasing mobility in and out of cities. The expected benefit to central business districts typically did not follow, however — for suburban visitors and workers, coming into the city became like a surgical strike, involving little interaction with the city beyond a specific destination.” It also describes another goal at the time. “Another goal of planners and city leaders at the time was slum clearance. To them, a slum often included any area of older buildings not lived in by wealthy people and any area where black residents lived, regardless of its economic or social value to its residents and patrons. Using urban freeway building as a reason for demolishing black neighborhoods was seen as accomplishing two goals at once — in other words, it was deliberate, not incidental.“

The is an interesting issue. If the history was reversed and I-375 had never been built, could the property owners successfully challenge the use of eminent domain to remove the neighborhood?

There are two types of agencies that can use the power of eminent domain. MCL 213.51 defines “public agency” as a “government unit, officer, or subdivision authorized by law to condemn property.” A public agency is provided with a much greater degree of judicial deference when a challenge to a taking is made. Per MCL 213.56(2), “with respect to an acquisition by a public agency, the determination of public necessity by that agency is binding on the court in the absence of a showing of fraud, error of law, or abuse of discretion.” (This post describes the greater flexibility that exists when challenging a private agency’s necessity determination to the extent that it was not ratified by a regulatory body).

These are generally difficult standards to achieve. Decisions from a planning perspective, including the best ways to move traffic efficiently and foster economic development, would need to be attacked as an abuse of discretion. In all likelihood, if history was different and MDOT was now planning to install I-375 instead of removing it, a court would be forced to defer to the agency’s determination even if it agreed with the logic of planners like the one quoted above.

However, one thing about this hypothetical project adds an extra twist. If the planning arguments were a pretext to engage in a racist policy of destroying and dispersing a historically black neighborhood, a fraud argument could be made. Further, under the Michigan Constitution, a taking for blight clearing must meet a higher standard to accomplish a public use. “In a condemnation action, the burden of proof is on the condemning authority to demonstrate, by the preponderance of the evidence, that the taking of a private property is for a public use, unless the condemnation action involves a taking for the eradication of blight, in which case the burden of proof is on the condemning authority to demonstrate, by clear and convincing evidence, that the taking of that property is for a public use.” Article X, § 2.

In all likelihood, an agency with the goal of eradicating blight, particularly if that goal was racially motivated, would not cite that as its public use or basis for necessity. This would tie more into the fraud argument, with an allegation that the planning basis for the taking was actually a pretext.

In any event, this is an interesting but hopefully academic debate as I have never observed a neighborhood being targeted for condemnation because of the race of its residents, as was historically done in the I-375 project decades ago.

If you have any eminent domain issues, please do not hesitate to contact me.